Editor’s Note: If you’re just picking up this story here, you may want to check out Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 that laid the groundwork for where we pick up the story.

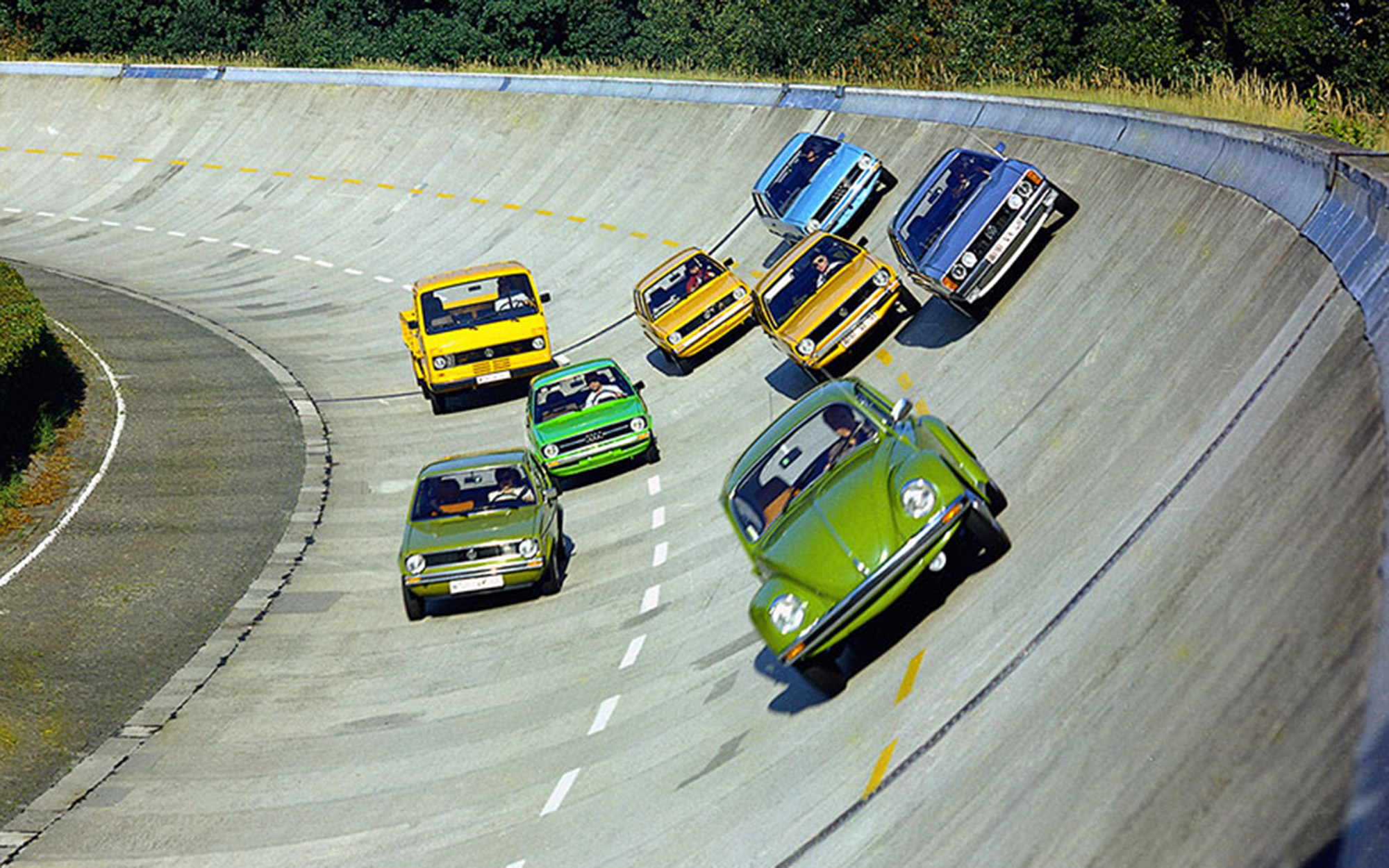

Maybe it should have been obvious that there would have been a downside to the overwhelming popularity of the World Rally Championship in the ‘80s and the Audi quattro’s early laying waste to its competitors. As Audi’s popularity quickly grew during those initial seasons, the team’s ability to test was becoming a real challenge.

In those earlier days, Audi had elected to test in Italy on the southern slopes of the Alps. The practice worked at first, but word amongst the enthusiastic Italians began spreading quickly, so much so that photographers and fans would turn up and get in the way. The team first counteracted that by bribing the local police (also massive rally fans) with stickers and memorabilia to shut down the roads.

Audi Sport also tested in Finland. Here, they’d work with local authorities to test on pre-selected gravel roads without too much hassle. Even here in the bitter cold though, photographers would inevitably find them. Some would go so far as to hide in trees in the test areas and wait to see if the team would show up with something new.

Things were getting out of hand. After an accident with a civilian car during a test in Italy, the need for a better solution was becoming apparent. At the same time, evolutions of the quattro such as the winged S1 E2 had even more need for sorting… and then there was the top secret mittelmotor project…

When Ferdinand Piëch and Roland Gumpert first conceptualized a mittelmotor solution to compete against more radical mid-engine projects from key rivals such as Peugeot and Lancia, they knew they had to keep it secret not just from the press and their rivals. They also needed to keep it secret from the board at Volkswagen who were keen to end Audi’s expensive rallying program altogether.

Of course, they’d need to test, and this presented a major hurdle. Volkswagen’s own remote test facility at Ehra-Lessien was out for obvious reasons. Built just miles from the East German border, Ehra Lessien was within a no-fly zone. Its sheer size also helped insulate from onlookers. What it didn’t insulate from though were those inside from Wolfsburg who would undoubtedly report on the Audi team’s testing of expensive-looking rally prototypes.

To Gumpert, it seemed as if practically anywhere in Western Europe had to be disqualified, because when the Audi Sport service trucks would turn up, they would inevitably draw a crowd. Even without those trucks with their giant tri-colore team livery stripes on the side, they’d still inadvertently put the call once they started testing because the rally quattros were just so loud. The distinctive bark of their 5-cylinder turbocharged engines at pace could be heard for miles. Under such conditions, curious onlookers, rabid fans and tree-climbing photographers appearing out of nowhere were only a matter of time.

Gumpert had to get creative, and for that he turned to his personal network. The shipping company that moved cars and parts for Audi Sport was headed by a man who had strong contacts in the east… as in east of the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia – then also named the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic as a satellite state of the Soviet Union.

It was there, in Dešná, a small town near Zlín and about 477 km away from Ingolstadt, that the JZD Slušovice facility was identified. The JZD acronym stands for “Jednotné zemědělské družstvo” or “United Cooperative Farm”. It was remote and about as secure as one might expect given its links to the local Communist Party. This meant the state and the secret police held a tight hold on happenings there.

Despite this association, the Slušovice agricultural cooperative’s activities were becoming more and more diverse. At its core, its business in by the 1980s centralized around the development of everything from biotechnologies to microelectronics. Beyond that, the JZD in Slušovice began establishing itself as a leader in embracing a consumer society, more open to diversifying its economic development in decidedly western ways. The facility constructed its own airfield, began holding horse races on Sundays in 1981, opened a trendy restaurant in a decommissioned airplane in 1982 and had begun building a luxury hotel in Všemina near the Slušovice Dam that would open in 1986. Foreign currencies were accepted in the area, while billboards on the walls of towns nearby were less prudish and more akin to the sex-sells advertising seen the west. Perhaps not coincidentally, the facility even operated its own rally team.

Some accounts suggest that it may have been Porsche who conceived the idea of project involving construction of a test area at the JZD Slušovice. True or not, it was Audi Sport’s testing budget that really saw it to completion. The Czechs were eager to learn competition skills from the Germans, particularly the preparation of competition cars and management of their own team that was competing in the domestic Czechoslovakian championship. In return, Audi was assured the secrecy it so desperately sought.

Several locations for the test course were considered. “We first offered the Germans a site near Podkopná Lhota for the construction of the polygon, but they didn’t like it very much,” said František Čuba, the then chairman of the Slušovice JZD for Leo Pavlík’s book Od Škodovky Po quattro. “It was exposed and very visible, you could see it from all sides. So, we had to keep looking.”

SIDENOTE 0001:

This book by Leo Pavlík is worth adding to any Audi rally fan’s library. It was invaluable in learning about this largely unknown piece of Audi history. While written in Czech, the Google Translate app makes reading it relatively easy. Find it HERE.

Special thanks to Leo Pavlík for permitting several photos to be included in this story.

After going through all the possible locations available in Slušovice, the group finally settled on a spot located on a wooded ridge outside of the small village of Dešná. The area featured few access routes with a narrow road up a hill that came in from the village, a configuration that would make it easy to monitor anyone approaching the area.

Ferdinand Piëch even traveled in to inspect the location. “We flew [him] from the airport in Klatovy to Moravia and then by car to Slušovice. I think he was quite shocked because he was expecting a classic agricultural enterprise, but instead he was welcomed here by ten deputies and directors in suits and ties,” states Czech rally star Leo Pavlík in his book. “I think he liked it here. He was surprised that such an enterprise could work here. He was also satisfied with the railway itself, especially liking the fact that its territory is well protected and that the cars on the track could not be photographed from the outside.”

Construction began on a test course or polygon, with design from the Germans and labor from the locals. When the area was prepared for construction, Dago Röhrer (head of development for Audi Sport) and test driver Walter Mayer came to view the progress. As Leo Pavlík tells it, the pair familiarized themselves with the area then hopped in their quattro and drove down the hill leaving a track in the grass. Behind them, a bulldozer cut the track in more permanently, with additional features such as an artificial ford and jumps being installed later. The gravel portions of the circuit came first, with the asphalt sections added later. The final layout of the course aimed to hark the roads around Sanremo.

Fencing was erected around the perimeter of the area housing the Děsná polygon Permanent workshops were also built, intended for the storage and repair of the Audi racecars themselves. Here, JZD Slušovice workers involved with the project were taught to obey instructions and keep quiet about the goings on.

Back in Germany, very few people at Audi knew of the Czechoslovakian project, and those that did were sworn to the utmost secrecy, avoiding even sharing it with their own families. When they’d depart Ingolstadt for initial tests, the team would carry documents for travel to Italy, while “Test Süditalien” would be stenciled on their crates.

For all their colleagues in the factory knew, the crews were headed to the south of Italy. However, once out of Ingolstadt the Audi Sport convoy would stop along the route for an encounter with a separate Audi operative who would hand them the proper passports and visas in order to enter Czechoslovakia. Roland Gumpert once told MotorSport Magazine, “I had a few good friends there, and the moment we went across the border we knew we were safe. We knew there wouldn’t be any photographers or journalists hiding in the bushes.”

They could rest more easily, confident that they weren’t being monitored by anyone including Volkswagen spies.

Construction wasn’t yet complete in Slušovice, but the team was keen to begin testing in Czechoslovakia anyway. So, while work continued on the polygon, Audi Sport began using locations closer to the German border. One of those earliest tests took place in a sandstone quarry in Karlovy Vary, and nearby field roads near Šumava Klatov. As with the Italian police, Czech police were similarly curious about the group’s activities with those incredible cars. Fortunately, they were also won over by gifts of team stickers and posters from the world-famous rally team.

By that summer of 1985, the polygon was completed and the Audi team settled into their new Dešná home. The track began to be actively used for stress tests ahead of individual rallies. For this task, the polygon was ideal.

The track’s layout was winding and tight, making it very difficult. This challenge proved valuable by intensely testing the durability of the Audi designs, improving their chances in notoriously brutal rallies such as the Acropolis Rally in Greece or Safari Rally in Kenya. It was in these races where reliability and durability shortcomings had hampered the quattros’ previous performances.

The team developed calculations of difficulty for each round of the World Rally Championship (WRC), with the Dešná polygon benchmarked as a coefficient of difficulty. For instance, if a component failed on a quattro following 83 kilometers on the Slušovice polygon, it equaled failing after 250 kilometers on a rally designated with the coefficient of three. Findings on component failure were documented in Dešná, directly resulting in implemented changes on competition cars being readied back at Audi Sport in Ingolstadt.

The first Sport quattro appeared in Dešná that summer of 1985 and it proved a challenge. Unlike the long-wheelbase quattros, early versions of the short-wheelbase car were unpredictable and didn’t want to turn. Test drivers found better control with the E2 when it arrived that September. Leo Pavlík, who was then getting seat time testing the cars, recounts his experience with the S1 E2 in his book, “Before the start of the test, Dago Röhrer, the head of development, came to me and said, ‘Let’s really test the car in all aspects.’”

“I went around the circuit first to warm up then came into the last left turn on approach to the jumping area at 100 percent, and it performed very well. So, I started to shift two full, three full, four full in the jump, and suddenly I see that I am passing the depot in the air and still not landing! Those huge spoilers and wings, instead of holding the car to the ground, created a cushion of air under it, on which I glided infinitely far and ended the test very quickly.

“Fortunately, the car was well balanced, so it didn’t hit either the nose or the rear. Even so, after the impact it jumped like a frog a few more times, and then we saw in horror – the engine broke loose, the shock absorbers punched up through of the hood. Dago watched the ground flight in disbelief and then just said that he didn’t really mean it with that jumping.”

Whereas the Sport quattro would usually jump roughly ten meters at full pace, the mechanics measured 56 meters for Leo’s jump in the S1 E2. From that day, test drivers had to be careful and let off before the jump, finding that a jump of 15 meters or so was a “piece of cake” for the S1 E2.

Leo and the other test drivers in Dešná were very quickly learning what the winged final evolution of the Sport quattro would become legend for. This S1 E2 was a monster, with 550 hp and capable of revving to 9,200 rpm. The car could blast from 0-100 km/h in about 2.8 seconds.

As development continued, local test drivers like Pavlík interacted with Audi factory drivers who visited regularly. Audi Sport’s lead test driver Walter Mayer was around so much that Dešná may as well have been his second home. The Austrian became so familiar with the course that visiting star factory drivers couldn’t touch his record on the polygon. German champion Harald Dumuth would regularly appear, as would Finnish driver Lasse Lampi who mainly focused on testing the experimental Porsche-developed PDK “sequential” gearbox-fitted Sport quattro.

Even Walter Röhrl visited several times, the multi-time world champion drawing admiration from the local Czech staff and drivers like Pavlík. Röhrl’s professionalism stood out in this group. Even if he was there to drive just five or six laps, he’d arrive in his racing suit and balaclava, whereas the regulars usually just drove in a T-shirt, their more casual garb augmented only by a helmet, gloves and racing shoes.

Interestingly, though Röhrl did visit on several occasions, he wasn’t there that day in 1985 when the odd-looking RS 001 turned up. But, that’s a story for the next installment.

NEXT UP PART 5: RS 001 TESTS IN DEŠNÁ

SOURCES BOOKS AND ARTICLES USED IN THE MAKING OF THIS STORY

Od Skodovky Po quattro, by Leo Pavlik

By Walter’s Side, by Christian Geistdorfer

“Audi’s Group S Prototype: The Lost 1980s Rally Monster” via MotorSport Magazine, by John Mallory

Okno do historie rally – díl 1. on Autosport.cz

“‘The Miracle of Slušovice’. The Municipality and the United Cooperative Farm” by Martin Jemelka