When Audi dropped its quattro all-wheel drive technology on the rally scene in 1980, it started a revolution. Though those first quattros at the end of the 1980 season couldn’t contend for points, the cars very quickly began winning races in 1981 once homologated. In 1982, Audi’s star driver Michèle Mouton may have narrowly missed the driver’s championship, but the Audi brand took home the manufacturer title. They’d do it again in 1984, though by that time they could see the competition had adapted.

Before the exotic new Group B Homologated Sport quattro had even turned a wheel in competition, some at Audi were beginning to come to grips with some hard facts. “We had some discussions in 1983 about which way we should go next, but Ferdinand Piëch wanted us to further develop the concept that was linked to the road car,” commented then team boss Roland Gumpert for a 2005 article in MotorSport Magazine. “The biggest problem with the quattro was not the engine, which was very strong, but the weight distribution and handling. So, the easiest way to correct this was to create a shorter car. That was the Sport quattro.”[1]

The Sport quattro was remedy Audi was able to prepare quickly, but not much of a remedy at all. It was lighter and had more power. There was less weight in the nose thanks to more composite bodywork and an aluminum engine block, but the short wheelbase made the car skittish and hard to handle. Also, understeer remained an Achilles heel. During his championship run of 1984, Stig Blomqvist preferred to compete in the more reliable long-wheelbase quattro A2 in order to better assure his victory.

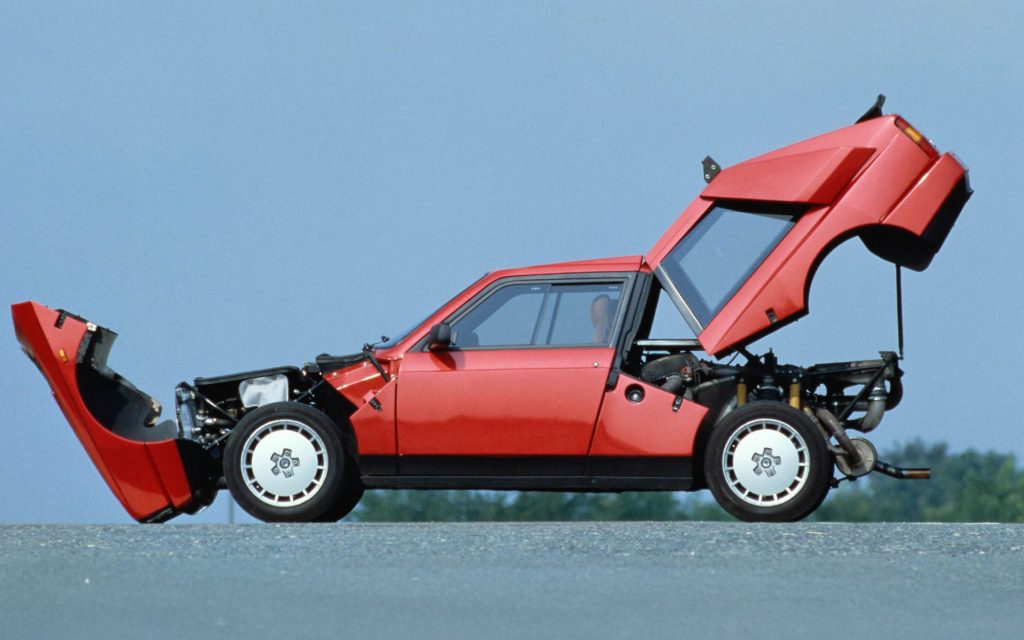

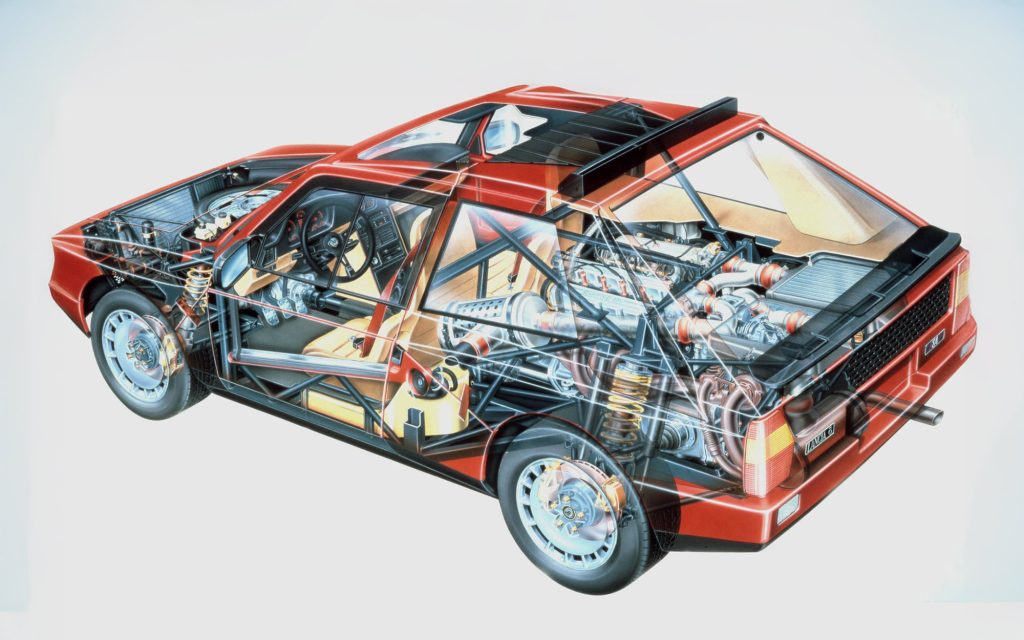

Walter Röhrl also commented on the Sport quattro for that 2005 article, “We’d known for some time that the Sport quattro was good on fast straights and fast corners, but the problem was the tight, slow corners – we had way too much understeer because there was too much weight in front of the axle. We saw from Peugeot that we needed to go mid-engined.”[1]

No pun intended, the Audi’s new Sport quattro (a.k.a. “S1”) faced an uphill battle. The car’s long 5-cylinder engine hung out over its front axle. The resulting maneuverability was becoming a hinderance against more balanced rivals. For some internally, the architecture that had been so dominating for Audi Sport was beginning to show itself as suboptimal when benchmarked on rally stages by these new competitors.

Mid-way through the 1984 season, Peugeot had arrived with its Group B homologated mid-engine 205 T16. Peugeot was throwing down a gauntlet in the rallying’s Group B category that other competing manufacturers couldn’t deny. Lancia would bring its Delta S4 later in the season, Ford returned after a rallying hiatus with its revolutionary RS200 and even MG had gotten in on the action with the Metro 6R4. Worse for Audi, momentum for the bonkers Group B rule set was snowballing with even more manufacturers were flocking to the sport.

If Audi didn’t adapt, it was sure to be left in the dust. Yes, the S1 had been their planned answer, but as you can see from Röhrl’s and Gumpert’s comments, many within the team weren’t certain their solution would be enough. Gumpert went on to say, “If the Sport quattro was the first answer, the second one was that in the longer term it could only be mid-engined..

Internally, team leadership lobbied management for additional resources to develop a mittelmotor (a.k.a. mid-engine) solution that would be an answer to the challenge being readied by their rivals. These requests were directed to the ears of none other than Ferdinand Piëch who, at the time, was head of Audi’s R&D and #2 at the brand in that moment.

Though he’s now known as an auto industry magnate of the highest order, it’s important to understand that Piëch at the time wasn’t all-powerful. Sure, as son of Ferdinand Porsche’s daughter Louise (Piëch) the ambitious and highly talented German was part of an automotive dynasty. He’d also proven his worth any number of times, more recently in that period at Audi when he’d championed the adoption of all-wheel drive to usher in a new era of post war and Volkswagen-funded rebirth and even segment dominance at Audi.

Whether he ever commented about it or not is unclear at the time of this writing but consider Piëch’s position. For starters, he had the leadership of Audi’s owners at Volkswagen to contend with. Though he’d eventually ascend to Chairmanship of the entire group, in 1984 Piëch was still just the #2 executive at Audi. And in Ingolstadt, Piëch was feeling increasing pressure from the VW bosses in Wolfsburg who were tiring of underwriting such an expensive rally program while watching Audi’s domination on the rally courses as anything but assured. Funds for the development of the S1 E2 had been approved, but nothing further beyond that.

Even internally at Audi, there wasn’t much support. After all, a pivot to a mittelmotor solution threatened the golden goose. The venerable quattro and its rallying success hadn’t just put Audi solidly back on the map. It had cemented the four rings as a serious contender against key luxury marques such as BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Porsche, making it the first and only brand to ever successfully shift from an economy brand to a credible premium brand.

In 1984, rally was wildly popular and Piëch had driven its reemergence home with authority…. figuratively and literally at the wheel of an Audi quattro. The brand’s marketing pitch was that every production quattro sold could be a potential rally winner. Admitting to the car’s faltering dominance against the more recent mid-engine competitors could risk eroding the ground that the four rings had come to occupy. Though Piëch was open to discussion, he knew to proceed with caution and not compromise Audi’s blister-flared moneymaker.

Still, Gumpert was firm in his beliefs. He also shared in that 2005 MotorSport article, “When all the other competitors were coming with mid-engined cars designed only for rallying it seemed to me, as an engineer, to be unfair. We had created a rally concept that was based on a front-engined road car, and it was now being compared to real, pure, mid-engined race cars. From a technical point of view, they had to be quicker.”

You have to wonder if his legacy and his namesake wasn’t also lost on Piëch. Likely it wasn’t. His long career shows example after example of his embracing new trends and technology with a keen understanding of the rich heritage available to him. Moving forward with an authentic consideration of history seems natural to him. So, when you’re the grandson of one of the world’s most legendary automotive engineers and your grandfather once championed mid-engine chassis design to dominate racing under the same four ring badge half a century before, does that weigh on your decision-making?

Piëch eventually conceded, giving his tacit approval. The Audi team got clearance to assemble a test car on one main condition. It had to remain a secret. He also wanted the development of a corresponding road car so that any associated rally dominance would directly correlate to cars being sold on the floors of Audi dealerships. Roland Gumpert had his green light, so he assembled a team, “We started work almost at the same time [as the Sport quattro], and by late 1984 we had a physical car ready to run.”[1]

In parrallel to Gumpert and his small team of Audi Sport engineers assembling evaluation mules by cobbling together existing components, a second small team of designers began to envision what such a mittelmotor quattro would look like in full production form. That group was led by former ur quattro design lead Smith who also tapped J Mays for exterior design.

Interestingly, FISA hadn’t finalized Group S regulations yet, and it’s quite possible that at this early stage Group S wasn’t even in the discussion. It’s also about this time Audi designer Peter Birtwhistle was in Switzerland finalizing the Sport quattro’s design. In theory, a version of the mittelmotor could have been ready early enough to compete in Group B should the stars have aligned.

All these moving variables would dictate some key decisions made by the two teams. For starters, they worked with existing drivetrain components. While Group S would likely render the existing Lehmann-developed 5-cylinder racing engine obsolete, it was too early to know what Group S would dictate.

Next, considerations for a production car would also require flexibility. Group B required 200 units to qualify for production. Based on the reported target sale price of DM 200,000 assigned to the project at the time, it seems Piëch likely saw the car as a Sport quattro successor and envisioned pricing it accordingly.

As Group S rules would begin to gel though, it was made clear that FISA planned a production run of just 10 to homologate. Whether or not Piëch knew of this or not and still desired a series of production akin to the Sport quattro isn’t clear. What we do know is that he was operating in that time under the homologation schema of Group B, which was 200 cars.

However this played out, Piëch knew that if he was to make a mittelmotor Audi happen, he’d need the greater support of the Board of Management at Volkswagen. The crafty German intended to show them a sorted car that would be so fast and potent as to be undeniable.

To be continued….

NEXT UP, Part 2: Mittelmotor Design Takes Shape Audi RS 001, the Mule

Source: Audi’s Group S prototype: the lost 1980s rally monster, by John McIlroy, MotorSport Magazine

Editor’s Note: Do you appreciate the premium Audi-focused content you’re finding via ooooIYKYK? This is a new content platform project in the Audi space, and its growth is critical in assuring its survival and growth. If you like what you see, please consider doing the following.

1.) Tell your friends.

Getting the word out to other Audi aficionados is key, and I’m trying to avoid spamming up online groups and forums in a painful display of self promotion. If I’ve earned your appreciation though, perhaps you can help the spread via word of mouth or recommendations by fans to other fans.

2.) As an Individual, Consider Subscribing.

Whether as a free subscriber or one who chooses to pay for a subscription to help fuel this platform’s existence, this is a notable way you can help. A newsletter distribution is managed via Substack HERE, where you can subscribe or pay for subscription even without being a member of Substack.

3. As a Company, Consider Sponsoring.

If you’re a business operating in the Audi space and open to underwrite quality content promoting the Audi brand, its cars and its owner enthusiasts, then consider underwriting ooooIYKYK. Elevating this project to a higher level of operation will not only augment the coverage and capabilities, they will directly and authentically associate your business as a patron of the Audi enthusiast space. If interested, please email george.achorn@ooooIYKYK.com for more information.