Editor’s Note: If you’re just picking up this story here, you may want to check out Part 1 and Part 2 that laid the groudnwork for where we pick up the story.

If the boxy Audi RS 001 was the test mule, the more rounded RS 002 was always the final plan. Sources for this story suggest the idea to design such a mid-engine rally car begin a bit earlier. Whereas the RS 001 test mules were assembled in 1985, the design project for what is today known as the RS 002 traces back to 1983.

What happened in 1983? Well, for starters Ferdinand Piëch and company at Audi Sport learned that quattro ain’t everything. Dominance in the World Rally Championship (WRC) had come on quickly, but a crafty opposition from Italy brought forth the mid-engined Lancia 037 and eeked out the manufacturer’s title despite not having all-wheel drive. Group B had begun, and the 037 was just the beginning. All-wheel drive opposition was being planned, but all-wheel drive installed in more balanced mid-engine packages.

Sidenote ooo1: One of the best features done by Jeremy Clarkson on The Grand Tour is almost certainly his retelling of the 1983 WRC battle between Audi and Lancia where the 037 took on the quattro. Prime Video Portugal has it on YouTube, not embeddable for this story though you can certainly watch it HERE.

Work had begun on the Sport quattro as the heat was turning up on Group B, but Piëch already knew that the Sport quattro was probably not the final answer (see also: Part 1: The Trouble with the quattro). For Piëch, continued dominance of the Audi rally program was critical to continue the repositioning of the Audi brand as a credible premium brand… and Piëch didn’t like to lose.

Back and Forth with BMW Design + Sport quattro Leaked + RS 002 Takes Shape

Due to the secrecy with which Ferdinand Piëch operated, it’s hard to know when work officially began on the design of the car that would come to be known as the “RS 002”. References from the Audi design team suggest it had already begun in 1983, which places it in almost the same timeframe as the Sport quattro.

It’s at this point the story gets even more intriguing. In 1982, a key Audi designer was about to leave. And, he wasn’t just any designer. Martin Smith had been at Audi since Hartmut Warkuss first set up a studio for the four rings in the post Volkswagen buyout, and in that time he’d effectively become Warkuss’ #2. Smith was responsible the design of the iconic “ur” quattro, and here he was leaving for BMW. Worse, he was taking several key Audi designers with him including young American talent J Mays. BMW had promised Smith a path to replace Claus Luthe, then head of design at BMW. This was a crippling hit to Audi at a critical time since it was still a very small team at a time when Piëch had very big plans.

Sidenote ooo2: Klaus Luthe, then at BMW, was himself a former Audi designer with a significant impact on postwar design in this early period at the brand. Designs attributed to Luthe include the NSU Prinz 4 (ergo TT/TTS), the NSU Wankel Spider, the Audi 50 and the C2-generaiton Audi 100/200/5000.

We know it’s about this time at the end of 1982 that the Sport quattro was also coming together. Hartmut Warkuss had dispatched designer Peter Birtwhistle in November to work out of supplier Seger and Hoffmann in Switzerland and finalize the short quattro’s design. Assigning him a nondescript VW Jetta to get there, Peter was to go finalize the S1’s design and then return just weeks later in time for Christmas. What Birtwhistle did there is covered in great detail in his biography An English Car Designer Abroad, though it’s worth pointing out he made it home in time for the holidays.

The following spring, Birtwhistle was sitting at his desk back in Ingolstadt when he was approached by Ferdinand Piëch and his boss Hartmut Warkuss. The two had a request, that Peter sketch the Sport quattro in the style of Auto Motor und Sport Magazine’s own in-house concept artist. Piëch instructed that, once his drawing was approved by Warkuss, Birtwhistle was to mail the sketch with no cover letter in an envelope he was provided. The mailing address was Los Angeles. Deducing it would likely end up in the magazine, Birtwhistle hid his name in the reflection on the car’s door in his drawing so he could prove to others it was his work in the magazine should it show up there.

And it did show up there, appearing on the cover and on a two-page interior spread of the June 1983 issue of the German automotive publication. The Sport quattro itself would debut weeks later at the Franfkurt IAA in September, though clearly Piëch was floating out information about the car by keeping the narrative going throughout that summer.

Maybe it was messaging the Sport quattro, but it also could have been to draw attention away from his other activities like an aggressive plan to get his design team back, successfully convincing Martin Smith and company to return to Audi within about three months.

Piëch would agreed to setting up the Audi Studio for Design Development (EDM) in the process, taking over space in an old Münich Renault dealership building. While this ruffled feathers back in Ingolstadt, it would be smoothed over in time. More importantly, Piëch had a young dynamic team that was also off site and at his disposal. This positioned them perfectly for taking on a top secret project, one he wanted to shroud even from internal corporate spies from Wolfsburg.

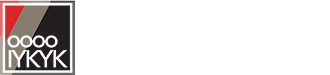

In Münich, Martin Smith assembled a small talented unit including J Mays for exterior design, plus Michael Ninic and Graham Thorpe for the interior. Bill Mitchell also joined, not the famed GM design chief, but rather Martin’s Bull Terrier by the same name.

As the RS 002 came together, the body would be 32 cm shorter than the ur quattro and a target price of 200,000 Deutsche Marks was envisioned. For reference, the ur quattro at that time cost 49,900 DM and the Sport quattro cost 203,850 DM. A base Porsche 911 would have run 26,900 DM while a 911 Turbo sold for 73,260 DM.

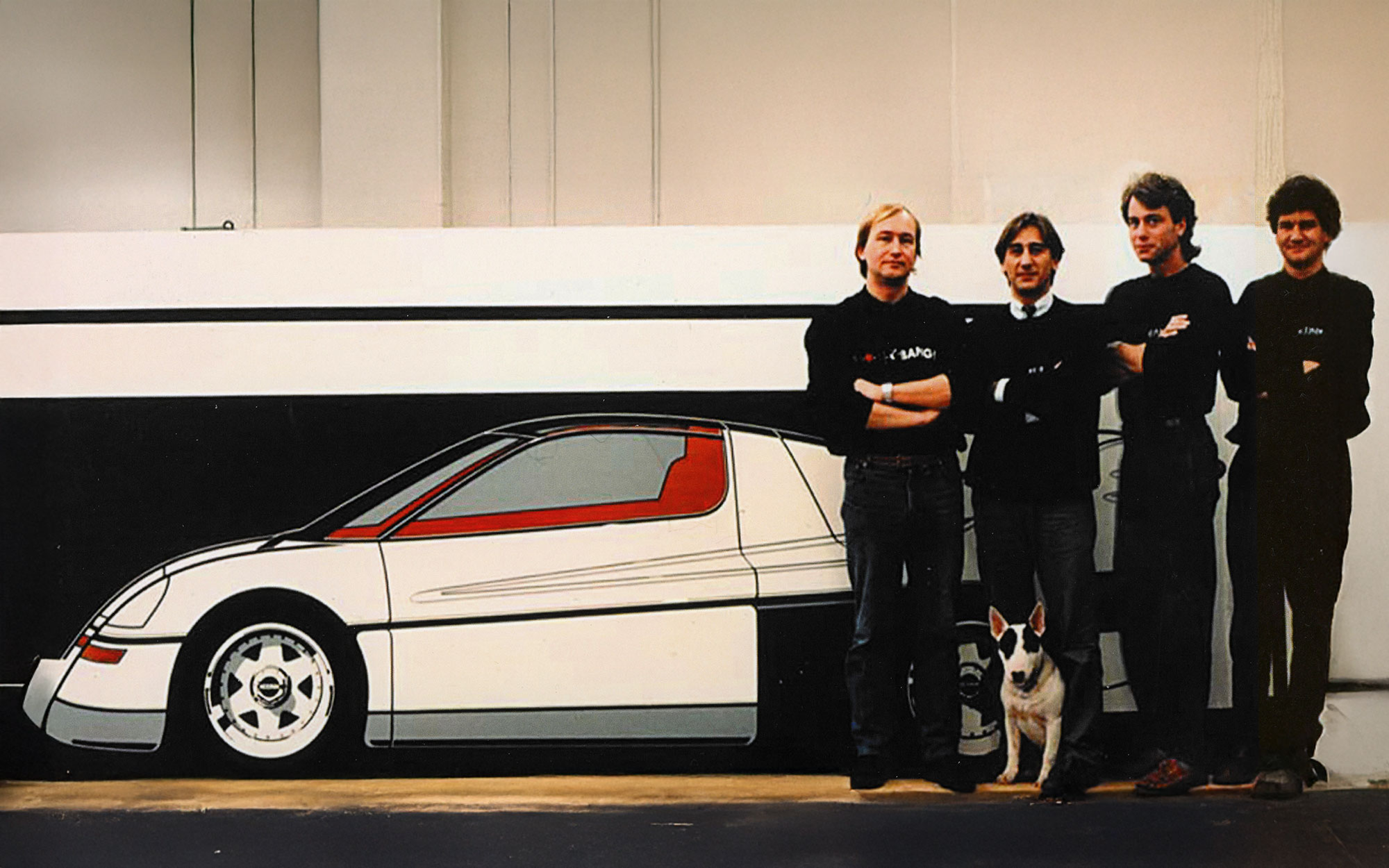

A surviving early sketch of the car’s exterior from 1983 and signed by J Mays is an interesting take on the car as it was first envisioned. Here, it is a bit more of a wedge. The proportions are animated in ways one expects of a design sketch, meaning always a bit more aggressive than reality. This is particularly noticeable where you see the shoulder height character line that cuts straight to the top of the rear wheel well, though it’s noticeably higher by the time the design evolves into the 1:1 scale model seen in the 1983 shot with the assembled design team.

Ferdinand & Walter

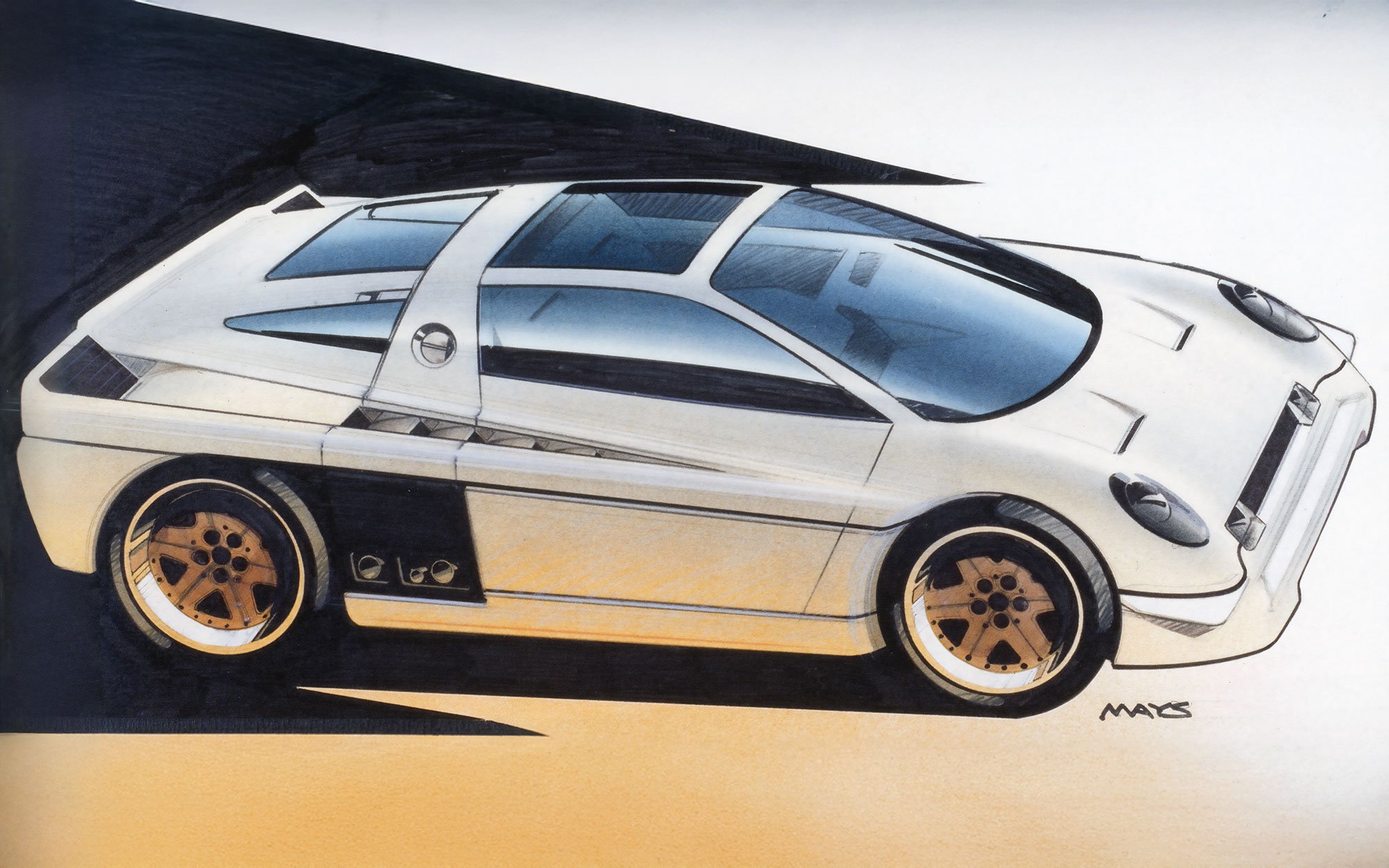

Continuing on his path of getting the right people for the job, Piëch had also been watching Walter Röhrl get the best of his team over two seasons. Though Audi had secured a manufacturer’s title in 1982 and a driver’s title in 1983, Röhrl had stymied Audi from sweeping both titles in the same years – first cementing the driver’s title in his Opel Ascona over Audi’s Michèle Mouton in her quattro during the 1982 season, then nabbing the 1983 manufacturer championship for Lancia at the wheel of the mid-engine 037. As Röhrl’s co-driver Christian Geistdorfer tells it, the thought at Audi at the time was, “better with Röhrl than against him”.

As the 1983 season was winding down, Piëch sent an emissary to approach Walter – none other than Robert Schwann, the manager of the great German footballer Franz Beckenbauer. Schwann applied pressure on Röhrl and Geistdorfer who themselves had already done the math, adding the undeniable dominance of all-wheel drive to Lancia’s lack of an all-wheel drive plan for the upcoming 1984 season. Talks between Audi and Röhrl proceeded, and by November 1983 the contracts had been signed.

This move had also ruffled some feathers at Audi, a team that tended to prioritize team success over individual driver success. By now Röhrl was a major star and came with a certain amount of expectations. At the same time, Audi Sport had three star drivers with a strong dynamic in Mouton, Mikkola and Blomqvist. Though some amongst the team were ecstatic to welcome Röhrl into their ranks, others including team boss Roland Gumpert were reportedly less enthused. There were too many drivers at this point, and something had to give. For the always pragmatic Piëch whose mission was to win, signing Röhrl was the logical choice.

Sidenote ooo3: Audi famously built the Sport quattro homologation cars in just five colors… well four really. 214 examples of the car were built: Tornado Red (128 ea.), Alpine White (48 ea.), Copenhagen Blue (21 ea.), Malachite Green (15 ea.). The tally indicates there were two more, painted black, with one going to Piëch and one going to Röhrl.

When the season began, changes to the team had followed. At January’s Rallye Monte Carlo opener, Michéle Mouton wasn’t one of the designated starting drivers and would only compete part of the season. That summer she’d turn up at Pike’s Peak to take on the legendary hillclimb in a specially prepared Sport quattro, winning her class while narrowly missing an outright victory.

In the meantime, the Sport quattro was proving itself unreliable in the WRC. Röhrl and his co-driver Christian Geistdorfer were frustrated, venting to Piëch. Geistdorfer shares what happened next in his biography By Walter’s Side.

“When Walter told Piëch about the chaos, the Audi boss reacted with disbelief at first. So, Walter suggested he take a look for himself. The week after Piëch turned up in Corsica for the new tests. From seven in the morning until seven in the evening, the top boss at Audi stood next to the car and watched his mechanics at work. He didn’t eat anything the whole time, drank maybe one bottle of water and burnt his bald head in the sun which was already quite strong in Corsica in April. The next morning, Piëch showed up at seven o’clock again and observed how the cars were being prepared for the tests. He asked to see some parts, but apart from that he hardly spoke. And when the sun got stronger again, he pulled out a handkerchief, made knots at the four corners and put it on his head for protection. It looked strange, to put it mildly, but that didn’t bother Piëch. Especially not in this situation. He was at the heart of the action. I found that very impressive. At about four in the afternoon, he announced that he had seen enough and was flying back to Ingolstadt, where those responsible took one hell of a bashing, by all accounts. An eyewitness told Walter and me later that it had felt like the earth was shaking.”

At some point, Röhrl and Piëch arrived in the studio, and it’s said that somewhere there’s a photo of the two of them looking at the car or more likely the tape drawing. At 6’5”, the German is decidedly lanky for a racecar driver and that’s one reason it’s attributed that the finalized greenhouse design for the RS 002 begins to become more bubble-like than Mays’ more wedge-like sketch.

Also in 1984, quarter scale models of the car were created, and it’s here that another priority around the car begins to gel. The boxy era was coming to an end and Audi design had more recently been focusing heavily on aerodynamics. For their road cars, this meant low drag coefficient for greater fuel economy. For race cars, greater downforce meant better adhesion in places Monte Carlo or the thin air of Pike’s Peak, topics that were both discussed as the design developed.

The scale models were tested at Porsche’s wind tunnel in Stuttgart, which likely accounts for what some refer to as a family resemblance. The RS 002 with its bulbous shape and notably large rear wing design are often compared to Group C cars at the time like the Porsche 956/962. Given what we know, perhaps it’s no surprise. Aerodynamic focus at the front and on that rear wing of the RS 002 was so effective that Audi engineers calculated they’d created enough downforce for the car to be driven upside down at speed should it drive into a round tube and change lanes onto the top of the tube.

Yet while the car was making great aerodynamic strides, it was also losing more and more cues from the original sketch. In the design models, we no longer see the distinctive B-pillar hoop, shoulder intake, lower more angular cabin and even what looks like an early take on the side blade.

As this chapter comes to a close, the calendar shifts to 1985. Work on a full-size prototype of the RS 002 had begun in Neckarsulm, yet still under the shroud of secrecy. Even more veiled were the activities of Roland Gumpert and his team constructing the RS 001 mittelmotor test mules. That group had crated the cars and was headed into communist territory where the mittelmotor RS 001 would experience its first top secret shakedowns on a test track hidden within a farm collective.

NEXT UP PART 3: WELCOME TO THE POLYGON. TESTING BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN

SOURCES BOOKS AND ARTICLES USED IN THE MAKING OF THIS STORY

An English Car Designer Abroad, by Peter Birtwhistle

Audi Design: Evolution of Form, by Othmark Wickenheiser

By Walter’s Side, by Christian Geistdorfer

Retrofuturism: The Car Design of J Mays, by Brooke Hodge and C Edson Armi

Audi’s Group S Prototype: The Lost 1980s Rally Monster via MotorSport Magazine, by John Mallory